The very first of The Ten Cardinal Precepts is, “I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” Though this precept sounds simple, it’s not. If there is a killing, one approach is to look to the person’s heart to understand how the situation relates to the precept. Someone may kill in the heat of an argument. Someone may kill in order to steal another’s possessions. Someone may kill out of a desire to conform to peer pressure. In the heat of an argument, one’s heart is consumed with anger. In stealing another’s possessions, one’s heart is consumed with attachment. And in conforming to peer pressure, one’s heart is consumed with delusion–the delusion that one person’s life has more or less value than another’s. In short, killing can arise from any of the three poisons–anger, attachment, or delusion. And in these cases, suffering will ensue. Any action borne of attachment, desire, or delusion has the potential to cause suffering.

“I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” The next scenario is as follows: a person breaks down a door and is wielding a weapon and clearly intends to kill the people in the room. Another person in the room is carrying a gun and has the opportunity to use deadly force to stop the attacker. The defender does so. Thing brings us to more questions than answers. Looking to the defender’s heart, was their action borne of anger toward the attacker? Looking to the defender’s heart, what their action borne of attachment/greed/desire? Looking to the defender’s heart, what their action borne of delusion? Can someone cherish life and yet kill another? Can someone kill another without anger, greed, or delusion? In this situation, is the defender cherishing the lives of the potential victims of the attack? It is not my place to offer an answer. The answer arises when looking to the heart and whether it was motivated by anger, attachment, or delusion, or whether is was motivated by compassion, contentment, and wisdom.

“I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” Cherishing life. Are we cherishing life when we are consumed by regret over the past to the extent we’re oblivious to what’s going on around us? Are we cherishing life when we are so consumed by worry that we can’t see what’s right in front of us? Are we cherishing life when we are consumed with fanciful thoughts of things as we want to be, rather than things as they are. When we are so absorbed that we are miles away from seeing things as they are, and being okay with things as they are, are we neglecting to cherish life; are we not killing ourselves every so slightly?

“I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” So many questions arise. So few answers. Look to the heart.

The very first of The Ten Cardinal Precepts is, “I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” It seems so simple. And yet it’s not. As with so many things, context is important.

Context #1. A person kills another to take their possessions out of desire. Context #2. A person kills a horse that has broken its leg; there is no way to get medical attention to the horse, and it’s suffering horribly. Intuitively, these are two very different situations. But let’s give the situations a framework. Is that action (killing) borne of attachment, anger, or ignorance? Or is that action borne of generosity, compassion, or wisdom? These are the three poisons and their antidotes, the three wholesome qualities.

Context #3. A soldier kills as part of his active duty in a war. Context #4. A solitary person is attacked and shoots in legally justifiable self defense. In these two contexts, are these people acting out of attachment/anger/ignorance or generosity/compassion/wisdom? It’s not that clear. And perhaps it’s not for us to decide–these people would need to look into their hearts to answer that.

Context #5. A person is at home with his family–a spouse and young children–when an armed person kicks down a door and starts shooting in the general direction of the family. The person in question draws his gun from concealment and fatally shoots the intruder. Is this person acting out of attachment/anger/ignorance or generosity/compassion/wisdom? I pose this question, but it is not for me to answer. Each of us has to look within our hearts and answer for themselves.

In these five scenarios, we’re looking at motivation. Clearly motivation is a factor. And yet “I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” still stands as the first precept, and this precept is not diminished by any motivation that might lead one to take a life.

I get funny looks when people find out I’m an NRA Certified Handgun and Concealed Carry Instructor and a Buddhist Lay Ministerial Student. The very first of The Ten Cardinal Precepts is, “I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life.” On the other hand, according to Washington State law, “Homicide is also justifiable when there is reasonable ground to believe there is imminent danger of great personal injury.” (RCW 9A.16.050 paraphrased.) Let’s back up to my childhood. I grew up in New York City in the sixties. Getting mugged on the streets of New York was a “normal” part of my childhood. Our apartment was burglarized. After we moved to Connecticut, our house was burglarized in the middle of the night. My brother heard the burglar, but thinking he was our father raiding the fridge late at night, walked in on the burglar who ran off, thank god. In White Salmon, right in my neighborhood, there was a series of home invasions by a local who was perpetually arrested and released. And by local I mean within walking distance.

I came to understand the concept of homo economicus or economic man. In a nutshell, this means that if someone wants a pair of expensive Nike sneakers, they could work, earn money, and buy them. Or they could rob someone of their sneakers or money with which they then buy the sneakers. In the first scenario, the cost is hard work. In the second scenario, the cost is the near zero probability of being caught. Clearly it makes more sense to steal the sneakers and/or money from a benefit/cost perspective. This is what I grew up with. Couple this with the fact that law abiding citizens are largely defenseless in New York City. I came to believe that being defenseless is unacceptable, and at my first opportunity, I got my concealed carry license in Connecticut many years ago. But guns kill. I hear that a lot. But being defenseless is unacceptable. Moreover, to impose being defenseless on another is unconscionable. There are people living in fear of domestic violence, stalkers, dangerous neighborhoods, dangerous commutes, and so on. So what does one do?

Let’s take a scenario that’s not far fetched at all. You’re at home with your family. Someone breaks down a door and runs in with a machete screaming, “I’m going to kill you all!” One would have reasonable ground to believe there is imminent danger of great personal injury. And the reality of the situation is that you can only choose from the options available to you. You can stand by and watch the intruder attack your family. Or you can use whatever force is necessary to stop the intruder. In that very instance, which rings more true, guns kill or being defenseless is unacceptable? Again, you can only choose from the options available to you.

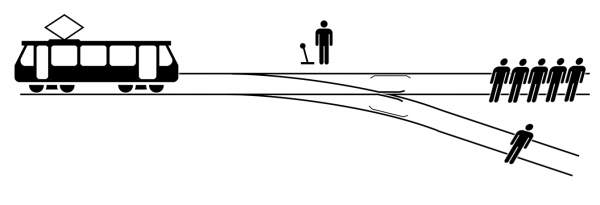

Now we’re getting into the territory of thought experiments, specifically the trolly problem.  For example, you’re standing at a lever that controls which tracks a train follows. The train is currently heading to a group of people. If you pull the lever, the train is diverted to the track on which there is only one person. As simple as this problem sounds, it quickly devolves as the scenario changes. Taking this problem a few steps down the road of murkiness, you’re a doctor at a hospital with five patients that need transplants. A hiker comes in with a broken ankle and he’s the perfect blood type match for all five patients. Similar scenario, and yet so very different.

For example, you’re standing at a lever that controls which tracks a train follows. The train is currently heading to a group of people. If you pull the lever, the train is diverted to the track on which there is only one person. As simple as this problem sounds, it quickly devolves as the scenario changes. Taking this problem a few steps down the road of murkiness, you’re a doctor at a hospital with five patients that need transplants. A hiker comes in with a broken ankle and he’s the perfect blood type match for all five patients. Similar scenario, and yet so very different.

Let me shift gears on you and introduce myself. I’m the thinking me. You’ve been reading the thoughts of the thinking me. The one who researches decision making theory. This person lived preeminently for most of my life. Now this person has taken a back seat to another person, the one who listens to his before thinking mind. This person is not concerned with historical perspective, thought experiments, statistics, and the like. This person contemplates, “What would I do in such-and-such situation?” And the answer is usually right there. That answer is neither right nor wrong. It just is. And the consequences that accompany any action that should follow are unavoidable, and or neither good nor bad. They just are. And are in accord with such action. Whatever we do, we own the consequences of our actions.

Circling back to, “I resolve not to kill, but to cherish all life,” is acting in self defense compatible with this first precept? Perhaps the answer is the same at Chao-chou’s answer to the question, “Does a dog have Buddha nature?” The answer is not as important as contemplating the question. Look beyond issues of right and wrong. Look into your heart and answer the question, “What you you do…?” listening to your before-thinking mind.

Leave A Comment